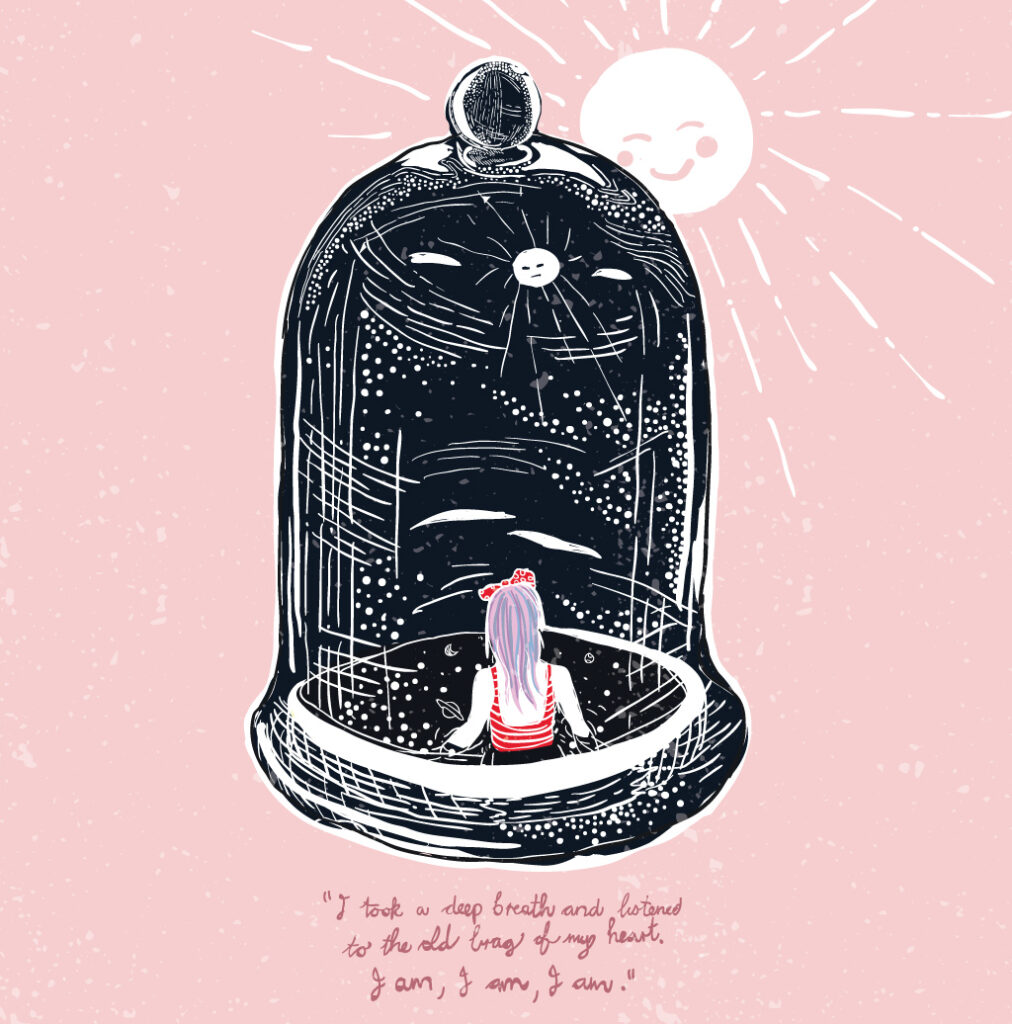

It’s been a few years since I first read The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath, but one scene has always stayed with me. Esther, suffocated and disconnected, goes to the beach with her friends and a boy suggested (she speculates) by her mother. She makes a silent and unannounced attempt to drown herself, but fails due to her body’s innate sense of self preservation. I imagine that, to her in that moment, the water felt like a portal to another world where the pain didn’t exist. The whole scene feels like a rather literal foreshadowing to the famous quote that appears at the end of the novel “… I am, i am, i am.”

It is the above moment in the book that I felt particularly moved to illustrate. A bathing Esther frozen in time deciding whether to drown herself, trapped under the titular bell jar. The world inside the bell jar seems more real, more textured than the flat distorted world outside. Through the deformations of the jar, the warm glow of the sun becomes too intense – even menacing. The sea around her becomes a black void waiting to envelop her, bell jar and all, absorbing her into its unknowable depths. Of course glass is transparent, and from some angles can even seem invisible to the naked, untrained eye of an outsider.

A novel that seems to have barely aged since its first publishing, The Bell Jar focuses on timeless human emotions. Throughout the first part of book, I identified closely with Esther Greenwood. Her seemingly unlimited ambition and her pursuit of writing struck a chord with me.

The story opens with Esther having secured a sought-after apprenticeship at a prominent New York magazine, Ladies Day, for the Summer. On paper it is the stuff of dreams and a gateway into the glamourous big-city life filled with beautiful and interesting people. Instead the experience falls flat and ends in Esther’s attempted rape. Giving up on her new glamourous life, she heads home to Massachusetts only to discover that she has been rejected from a writing course taught by a famous author. She half-heartedly decides to spend the time instead writing a novel, but soon devolves into a full-blown depression.

Being a brand-new, freshly-minted young adult is at best an exciting time full of unknowns. At worst this period is an absolute identity crisis as we are thrust into the world kicking and screaming, ready or not. There is a vagary during this time of our lives where we begin to confuse things we are merely good at for things we truly enjoy. Not that the two are necessarily mutually exclusive. Long years if praise for her writing and consistent excellent grades may have played a part in Esther’s confusion and turmoil when it came to taking the next step in her career. Disillusioned with big city life, and failing to get into her desired tertiary writing program, suddenly the thing that always seemed so sure, so infallible – Esther’s writing – failed her. What is one to do when one goes from being a big fish in a small pond to an underwhelming fleck of plankton in the ocean?

As time progressed within the novel and the layers of Esther’s personality revealed themselves, the identification grew stronger. I believe that Esther’s struggles still hold true today, and that the parallels we can draw between her thoughts and the contemporary notion of the quarter life crisis are uncanny. Esther is an over-achiever. She has cracked the code and routine of school. So ingrained in her is the ritual of getting good grades, that by the end of the ordeal that is the education system, she has lost herself.

Esther also seems to have a split personality regarding her life goals. One feels the strong pull of the social conventions of the time (ripples and echoes of which can still be felt today.) Esther has the constant need to date. To find an other. To get “it” over with. To tick the box of marriage. She yearns to be conventional. Yet the other Esther shuns the ordinary. She wants not children nor husband. Her revelations and questions are strikingly modern and feminist – yet there is that pull to be normal and disappointment (and later acceptance) that she is not.

It is at this point that Esther is sent off to a psychiatrist at the behest of her mother where she is treated to electroconvulsive therapy and is sent further into a downward spiral. The titular Bell Jar compares both depression and the expectations of society at large to being trapped inside a bell jar. The combination of stagnation and suffocation is overwhelming. The soundless void inside blocks out any external voices of reason that may try to penetrate, the outside world distorted by the glass into something unnerving, strange and untrustworthy.

As Esther describes it:

“If Mrs. Guinea had given me a ticket to Europe, or a round-the-world cruise, it wouldn’t have made one scrap of difference to me, because wherever I sat — on the deck of a ship or at a street café in Paris or Bangkok — I would be sitting under the same glass bell jar, stewing in my own sour air. ”

-Sylvia Plath, the Bell Jar, Chapter 15

And in the last chapter, “To the person in the bell jar, blank and stopped as a dead baby, the world itself is the bad dream… How did I know that someday—at college, in Europe, somewhere, anywhere—the bell jar, with its stifling distortions, wouldn’t descend again?”

Esther can lift the bell jar enough to breathe perhaps, but perhaps it will always remain hovering, tense and ready to trap her once more if she isn’t careful. Sylvia Plath herself succumbed to the vacuum of the bell jar in her early thirties.